Re-Dock intern, (and now librarian – edited 2014) Becky Mulvaney discusses the her research through own relationship to libraries, developed early on thanks to her Grandmother’s weekly trips.My Grandmother visited her local library, unless the weather was particularly dire, every Tuesday. This weekly pilgrimage to exchange one book for another persisted for over two decades. Why she devoted this trip to a Tuesday is beyond my reckoning, though I could guess that it was because every other day was already ascribed a task (washing, gardening, bathing etc) and she was a woman who lived by routine.

Library-day was often the highlight of my pre-school years and thereafter, every long Summer holiday which I spent at her house. This was not only because we went by bus, which my four year old self thought to be a great adventure, but because I believed that all the books in the world lived in that particular, tiny, library.

Even the books in my Grandmother’s dining room, closeted inside a very dark, very wooden, glass-fronted cabinet, had library tickets glued to the insides of their first pages. Years later, when I realised how odd this was, it was revealed that my Grandfather had been a notorious hoarder, who was banned from said library after en-massing an impressive collection of ‘overdue’ print.

Presumably, being able and encouraged to access a variety of resources; literature, audio-books, games and later, computers, for free throughout my childhood, will have enriched my character and quality of life. We were not a wealthy little family, but I was spoiled rotten with books.

As an English student, I use the University of Liverpool’s Sydney Jones library (both digital and physical collections) at least once a day. Without which I would be bankrupted by the cost academic tomes and journals. I also regularly utilise the free e-books made available by Project Gutenberg to download most of the texts which crop up on my reading lists. Although they are increasingly seen as ‘throw-away’ items, I do not believe that the books sold in high-street stores are cheap.

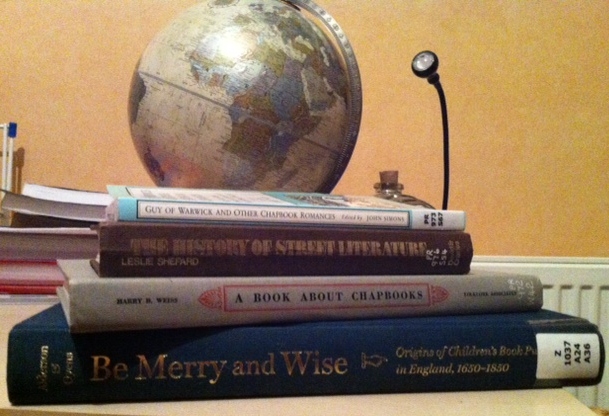

On the subject of reading; it seemed sensible to familiarise myself with the history and production of Chapbooks before delving into the Special Collections & Archives; who, on an unrelated note, have launched their very own blog today.

My research began by combing through the University’s library database and then staggering from aisle to aisle, trying to balance an insensibly heavy pile of hardbacks on one arm. I did not expect texts which concern themselves with such small printed objects to be so obscenely large, but I was glad to lug them home and peruse their pages.

Through my initial reading, I have been especially interested to learn that Chapbooks were not the printed literature of the uneducated, as has been wrongly assumed by some scholars in the past, but the only form of print which agricultural and urban laborers could afford. Even then, it was probably only the more comfortably-off of the working classes who could afford to buy Chapbooks on a regular basis.

Being poor does not mean that you are unintelligent, but it does restrict your access to prestigious resources and books in the 17th & 18th centuries were very expensive to purchase. Laborers could not necessarily invest their time in education, even when it was freely available, since nearly every hour of their lives was spent earning enough to survive. However, those who could read would often do so aloud so that members of their family or community could share in the experience.

Imagine a world in which it was a luxury to own a printed publication, no bigger than a single piece of broadsheet newspaper, despite your ability to read. As it is unlikely that we are all descended from the affluent upper classes, this was the reality for most of our ancestors.

As my research into Chapbooks continues, I am reminded of how fortunate I am to be living within a society which provides opportunities for education, and services such as public libraries, which enable people to access resources such as literature and technology, for free.